For nine long years, 1939-47, a slow-growth period in which Amphitheater High School played in six-man football and in the stateŌĆÖs B League against low-caliber competition such as Ajo, St. David and Tombstone, Tucson High School won state football championships in 1942, 1943, 1944 and 1945, becoming the kingpin of ├█┴─ų▒▓ź prep football.

The Star described AmphiŌĆÖs new football program as ŌĆ£the pint-sized high school in the pasture lands north of Tucson.ŌĆØ

But when Amphi was moved to Class A status in 1947 and was added to TucsonŌĆÖs imposing football schedule, everything changed. Tucson was no longer a one-team football town.

Tucson High Magnet School,┬Ā400 N. Second Ave.

In August 1947, prominent Tucson businessman Roy Drachman ŌĆö the man credited with bringing spring training baseball to Tucson ŌĆö proposed that Tucson stage a high school football ŌĆ£Game of the Year,ŌĆØ a postseason epic between eight-time state champion Tucson High School and the cityŌĆÖs new high school, Amphitheater.

People are also reading…

Drachman boldly predicted the game would draw more than 10,000 fans; proceeds from the postseason showdown would be divided between Tucson charities. ŌĆ£The game might eventually draw 15,000,ŌĆØ Drachman said.

The ├█┴─ų▒▓ź Interscholastic Association prohibited postseason games, but Drachman persisted. He had a vision that TucsonŌĆÖs second high school, Amphi, could someday rival the Badgers as a state power and appeal to Tucson sports fans.

Alas, long-time THS football coach Rollin Gridley objected. ŌĆ£Rules are rules,ŌĆØ he told the Star. ŌĆ£We will stick by them.ŌĆØ

Gridley, whose Badgers had won four consecutive state championships, thought the BadgersŌĆÖ schedule was already tough enough. They had played games in Southern California three years in succession, as well as another in Austin, Texas. The grind of playing Phoenix-area powers St. MaryŌĆÖs, Mesa and Glendale was taxing enough.

And although the AIA denied DrachmanŌĆÖs proposal to schedule an Amphi-Tucson game on Thanksgiving Day, Amphi was added to TucsonŌĆÖs regular season schedule in 1948. It would become one of the most intense prep football rivalries in Tucson history, then or now or anytime.

Amphi hired former ├█┴─ų▒▓ź all-conference lineman Murl McCain as its coach in the summer of ŌĆÖ47, and in the yearŌĆÖs last game, he played state champion Mesa to a tight finish, losing 20-14. The newspapers referred to him as ŌĆ£Maestro McCain.ŌĆØ

Ahead of the first-ever Tucson-Amphi game in September 1948, the Tucson Citizen wrote: ŌĆ£For those who missed the Fourth of July fireworks, there will be plenty of them in the Amphi-Tucson game to satiate even the most bang-bang admirer.ŌĆØ

The expectations turned out to be true.

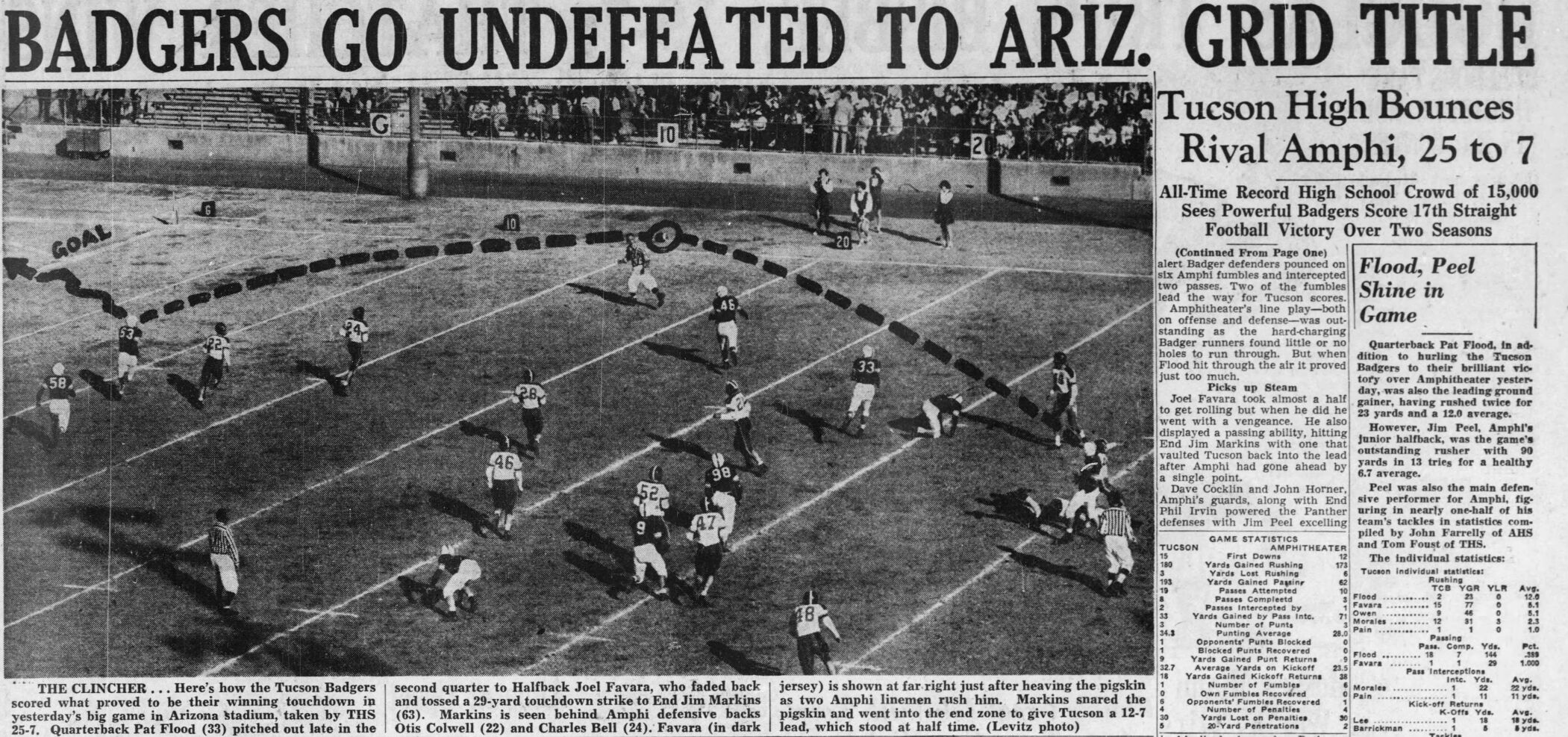

Tucson won the inaugural game, 21-12, played before an overflow crowd of 10,200 at Tucson High, but a year later, McCainŌĆÖs Panthers stunned the Badgers, 13-12. The rivalry was on. Tucson High fans painted some of the walls at Amphi red before the 1950 game. In 1957, Amphi fans painted an A on TucsonŌĆÖs playing field.

The game was moved from September to the last game of the season, Thanksgiving week, and for the next dozen years, sellout crowds of 10,000 or so were routine. Even though Red Greer coached Tucson High to back-to-back state championships in 1951 and 1952, McCain kept much smaller Amphi ŌĆö THS enrollment in the early ŌĆÖ50s was estimated at close to 4,000; AmphiŌĆÖs was 1,000 ŌĆö competitive, with future Pima County Sports Hall of Fame brothers Larry Hart and Bob Hart playing the starring roles.

Star columnist Abe Chanin wrote that the rivalry had ŌĆ£the city a-buzzing.ŌĆØ

Tucson High wrapped up its perfect season in 1952 by routing Amphitheater.

One year, the Tucson High band marched in a downtown parade at noon. At 3 p.m., the Amphi band marched down the same street. ŌĆ£It shook the rooftops of the city,ŌĆØ the Star wrote.

As with any true rivalry, tensions grew. In 1955, Tucson High fans hanged McCain in effigy from the goalposts at Amphi. The Badger fans left a sign that read ŌĆ£We like Panther meat on Turkey Day.ŌĆØ

A day later, Amphi upset Tucson, 6-0. Said McCain: ŌĆ£We wanted to beat them too much to put into words.ŌĆØ

McCain retired from coaching in 1959, moving home to Yuma to sell real estate. Greer left the Tucson High coaching job in 1956. The rivalry changed as Amphi hired five unsuccessful coaches until they brought on future state championship coaches Jerry Loper (1973) and Vern Friedli (1975).

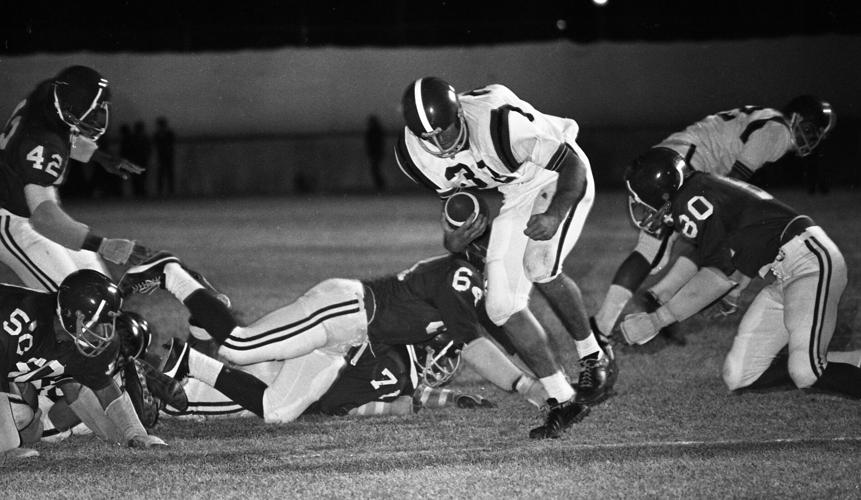

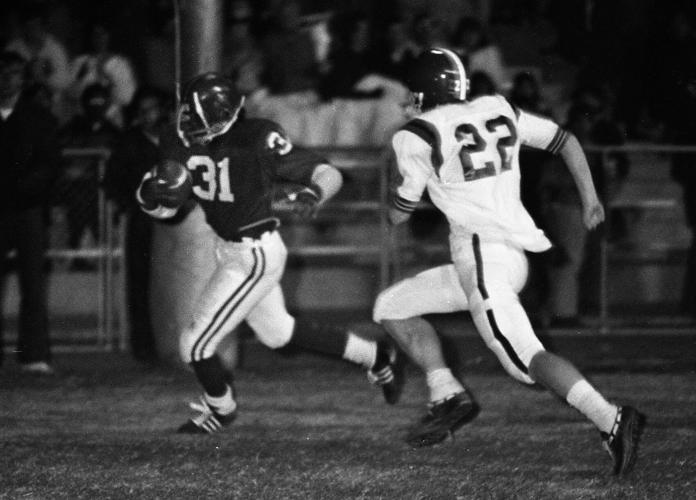

Tucson High School trounced Amphitheater, 57-22, on Oct. 29, 1971. Amphi was undefeated in league play that year.

The once canŌĆÖt-miss rivalry ebbed. Some of it was coaching, but most of it was TucsonŌĆÖs growth. Amphi and Tucson had been the only game in town ŌĆö the must-see showdown ŌĆö for almost a decade, but Salpointe began playing varsity football in 1956, followed in 1957 by Pueblo and Catalina, and by Rincon in 1959 and Sunnyside and Palo Verde, both in 1962. The cityŌĆÖs best rivalry would never be the same.

Tucson High hired John Mallamo to succeed Greer; Mallamo won state titles in 1962 and 1965. Mallamo was succeeded by Ollie Mayfield, who won back-to-back state titles in 1970 and 1971. Amphi faded for a decade.

By the 1970s, new schools Sahuaro, Sabino, Santa Rita, Cholla, Canyon del Oro and Flowing Wells had joined the scene. New rivalries bloomed and then faded. Sadly, Tucson High lost 21 consecutive games to FriedliŌĆÖs powerhouse Panthers from 1973-93. That 0-21 streak ended in 1994 when Todd Mayfield, OllieŌĆÖs son, coached THS to a stunning 34-21 victory over the Panthers.

ŌĆ£After the game,ŌĆØ Todd Mayfield said last week, ŌĆ£Vern Friedli walked over, shook my hand and said ŌĆśstreaks are made to be broken, and you just broke us.ŌĆÖ But the game had changed, it evolved almost every year with the infusion of all the new schools. But the old Amphi-Tucson rivalry was probably as good as it gets in Tucson.ŌĆØ

Tucson High School trounced Amphitheater, 57-22, on Oct. 29, 1971.

By 2001, as the AIA moved from three classifications to four, five and now six, Amphi and Tucson ended their long on-field football rivalry. They have not played one another since 2001.